By John Symons

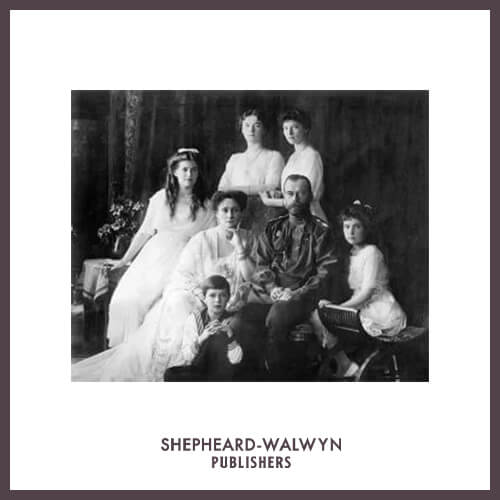

The last Tsar of Russia, Nicholas II, was born one hundred and fifty years ago. One hundred years ago, on 17th July 1918, he, his wife and their five children were murdered by the Bolsheviks. With our constitutional monarchy, there are many lessons for us here.

Who can forget the scenes filmed in 1994 in St Petersburg, recently reborn in its original name after seventy years as Leningrad, when our Queen visited Russia on a state visit? President Yeltsin had many faults but it was he who gave Russia her only brief years of freedom in the last century after Lenin, Trotsky and the Bolsheviks seized power in October/November 1917. President Yeltsin stood aside in a subdued and reverential way as the Queen paused for what seemed an eternity at the tombs of the Tsars.

It had been President Yeltsin who had taken the decision, when he was still a Communist regional leader in 1977, to raze to the ground the building in which the Tsar and family and their servants had been murdered, in order to remove a place of pilgrimage of some Russians who had never accepted Communism. Now he had the opportunity to atone for that evil action. He did so later in 1998 by authorising the reburial of the last Tsar and his family in St Petersburg. It was a brave decision, opposed by the Communist Party, still strong at that time.

With President Yeltsin’s departure, and Putin’s coming to power, true Russian liberty has again been lost, this time in a wicked authoritarian parody of democracy.

It need not have been so. In the years 1905 to 1914, because of Russia’s defeat by Japan in the Far East and grave social unrest, Tsar Nicholas agreed to a Constitution and the beginnings of Parliamentary democracy. The process was imperfect and the Tsar’s wife, a German Princess who shared Kaiser Wilhelm II’s malign attitudes, did all she could (and it was a lot) to thwart these tentative steps. There was an exchange between the Westminster Parliament and the Russian, called the Duma. The British and Russian Royal families maintained links and exchanged visits in 1908 and 1909. It was a beginning, cautious and shaky, but it might well have led to Russia’s becoming a constitutional monarchy and a Parliamentary democracy, a rich and free country, at peace to the east of Europe. How different the world would have been.

Everything was destroyed by the Kaiser’s determination on power which led to the War in 1914 and then by Lenin’s use of that War, with the help of German money on a grand scale, to impose Bolshevik rule and tyranny on the Russian Empire. As Lenin put it, ‘We must turn this Imperialist war into a civil war in Russia and so achieve power.’ He did so.

So who decided to murder the Tsar? It was Lenin. All Bolsheviks yielded supreme authority to him. Only Trotsky at that time neared him in power, but he always deferred to Lenin when the two disagreed.

As it happens, it is Trotsky himself who tells us that Lenin took the decision. Trotsky was not in Moscow when Lenin decided the matter, but away at the front leading the Red Army against the Whites. On a visit to Moscow soon after the seventeenth of July 1918, Trotsky met Sverdlov, one of Lenin’s most ruthless colleagues, used by him to deal with many vile matters. In his diary, Trotsky records his conversation with Sverdlov:

In passing I asked Sverdlov, ‘But where is the Tsar?

‘Shot, of course.’

‘Where is the family?’

‘The family was shot with him.’

‘The whole family …?’

‘Yes, all the family,’ Sverdlov replied. ‘Well …?’

Sverdlov waited for my reaction. I made no reply.

‘But who took the decision?’

‘Here in Moscow we decided. Lenin (Sverdlov refers to him in intimate terms, using solely his patronymic, Ilych), Lenin calculated that it was not possible to let him live, especially in the present difficult conditions (in the civil war the Whites were advancing and gaining support.)

Trotsky adds his own comment, that he thought the decision essential and well directed. At the time the Soviet authorities stated publicly that the Tsar was the only person killed, and denied the role of Lenin and his colleagues in Moscow in the murders. This they did to protect his image in the West, where many ‘useful idiots’, as he called them, revered him. The Bolsheviks claimed publicly that the Tsar’s family had been evacuated to another place because of the Whites’ advance. It was all of a piece with the countless lies told by Soviet leaders for their seventy five years in power.

Lenin himself wrote that it was vital to kill the Tsar and his family in 1918 and to implicate all Bolsheviks in the deed. Only if that were done, he reckoned, would the weaker minded Communists realise that there could be no turning back from achieving total power.

And, indeed, Lenin was right. In the Tsar, as in our monarch, all authority, civil and religious, meets. In our case, with a constitutional monarch, authority and power are delegated and spread. In Russia in 1918, that process of disseminating power was only beginning. To the ninety nine per cent of Russians who were not Bolsheviks, the Tsar in himself symbolised their country to a degree that we can scarcely conceive.

Only at the Coronation does it become clear here what is involved. At that service in 1953 we saw the solemnity of the authority entrusted by God to the Queen, as the ceremonies of anointing and crowning took place. With them, the Queen took vows that no one would contemplate unless chosen by destiny to face them.

Perhaps in 1994, as she stood so long in silence by the tombs of the Tsars, the Queen was pondering this. For she is one of the few people alive, perhaps the only Christian monarch alive, who can understand, to the full, the nature of those vows which, for all his weaknesses the last Tsar, like the Queen, took so seriously.

John Symons is the author of A Tear in the Curtain.

“A Tear in the Curtain is the history of Russia, but in a form that you will not have read it before. It is at the same time objective and intensely personal. It tells us more in a few pages than many more formal accounts manage in a whole volume … full of insight, inspiring, and leaving one with the conviction that Russia’s renewed betrayal of its moral values can be only a passing phase.”

Michael Bourdeaux, founder of the Keston Institute, Oxford, a distinguished expert on Russia and its history, faiths and peoples.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.