By Coryne Hall

News of the murder of Nicholas II hit the 69-year-old Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna like a thunderbolt.

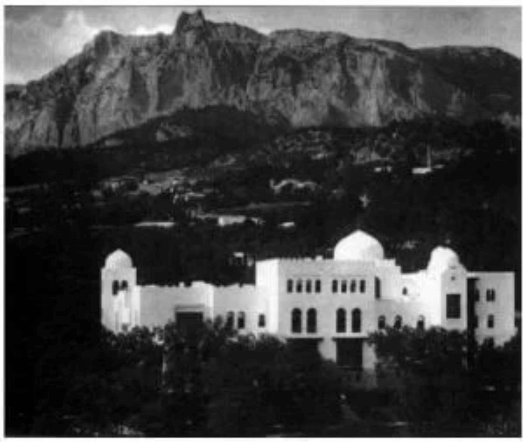

In the summer of 1918 she was living in German-occupied Crimea, where until May she and her family had been held under house arrest by the Bolsheviks. But throughout most of this time she had managed to stay in contact with her son the Tsar. Her last letter from him had been in March.

While Nicholas, Alexandra and their children were in captivity in Tobolsk letters were sent by trusted couriers. With the aid of two loyal officers, a young girl and various friends along the route, letters and parcels were smuggled to and from Tobolsk at great personal risk. These letters did not go through the hands of the official censor.

One of these couriers was ‘Domna’, or ‘Domnouchka’, a thirty-five-year-old Russian peasant with long blond plaits which earned her the nickname of ‘little tresses’ among the Imperial family. She carried letters sewn into a chiffon pouch on her breast. Sometimes she managed to hitch a ride on a cattle truck or goods wagon but most of the time she walked.

Through these couriers contact between the Crimea and Tobolsk was maintained until the following spring. Then letters arrived from Nicholas’ daughters, from which it appeared that they had been separated from their parents. In April Nicholas, Alexandra and Maria were moved to Ekaterinburg in the hostile Urals and imprisoned in the house of the merchant Ipatiev, ominously renamed ‘The House of Special Purpose’. Conditions were bad. The other children remained at Tobolsk while Alexei recovered from a haemorrhage, his worst illness since the one he suffered at Spala in 1912.

Early in May the courier known as ‘tresses’ disappeared. Ten days later there was still no news of her whereabouts. During the spring she had left the Crimea with letters and some Holy relics; by the time the package reached Tobolsk the children had rejoined their parents. The link with the Crimea was broken.

By the end of July the uncertainty about Nicholas was becoming unbearable for Marie Feodorovna. Then on 1st August telegrams from Kiev broke the first official news that Nicholas had been shot on the night of 16/17 July but that Alexandra and the children had been ‘sent to a safe place’.

The Dowager Empress did not believe that Nicholas was dead and expected Empress Alexandra and the children to be sent to the Crimea. She refused to attend the Requiem held at nearby Ai-Todor and, out of deference to her, no other members of the family attended either. She insisted Nicholas was alive and that the picnic organised for the following day should go ahead.

When her nephew King Christian X of Denmark wrote to express his sympathy, the Dowager Empress replied in October:

“Thanks be to God that the most terrifying rumours concerning my poor beloved Nicky seem to be untrue. After several weeks of terrifying suspense and proclamations, I have been assured that he and his family have been released and brought to a place of safety. You can well imagine how I thank the Lord with all my heart. I have heard nothing from him myself since last March when they were still in Tobolsk, so you can imagine the terrible time I have experienced through all these long months even though, in my heart of hearts, I have never given up hope or believed the dreadful rumours. Now that I have heard from several sources [that Nicholas was alive], I have to hope that it is true, so help me God.”

In the absence of any proof that they were all dead, rumours flourished but the Dowager Empress never heard from Nicholas or his family again.

Marie Feodorovna died in her native Denmark in 1928, still refusing to admit that Nicholas and his family had been killed in the Ipatiev House on that hot July night in 1918.

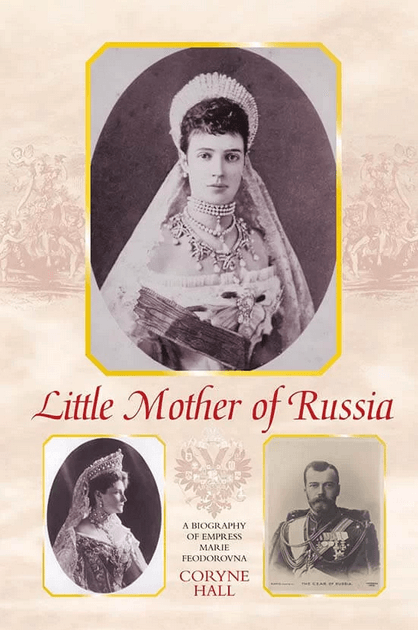

Coryne Hall is the author of Little Mother of Russia: A Biography of Empress Marie Feodorovna. For more information about her writing career visit her author page.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.