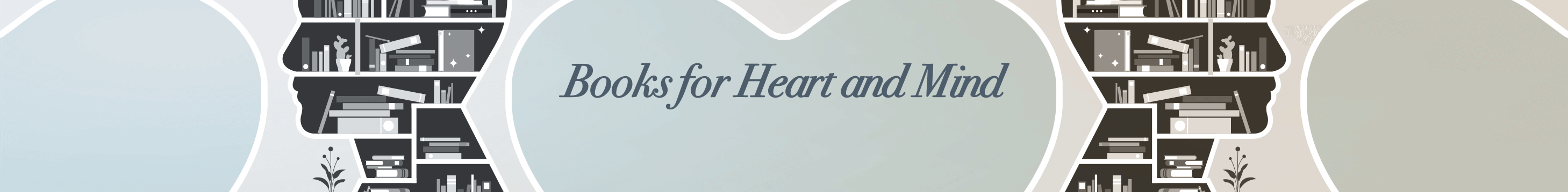

Description

‘The greatest labouring-class poet that England has ever produced.’

Jonathan Bate on BBC In Our Time with Melvyn Bragg

John Clare (1793-1864) was born at a time of great social upheaval, just months after the beheading of Louis XVI and the outbreak of war with France which was to last till the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815. He also lived through the upheavals of the land enclosure movement and agricultural revolution which changed the face of the countryside and the way of life in rural England.

His father was a farm worker who managed to pay for his son’s schooling, though this was cut short as conditions worsened, but at least Clare had by then learnt to read and write so he could continue his own education, reading whatever books he could lay his hands on. At the age of sixteen he witnessed the social dislocation caused by the local enclosure Act and observed how the landscape was gradually transformed. Drawing on Clare’s writing, this extensively researched study gives the modern reader an appreciation of the divisive effects of these policies.

Structured chronologically, this exploration of John Clare’s life highlights the socio-economic and environmental aspects of his observations and includes his reports on an insidious revolution taking place in the English countryside. Parliament, dominated by landowners, authorised the enclosure of large tracts of common land by private acts without considering the effect on those who had enjoyed rights of use and pasturage for centuries.

Land enclosures, and the improved agricultural techniques which this permitted, was important in increasing food production at a time when the population of England was growing rapidly. While additional work was initially provided for agricultural labourers in the fencing and walling needed, this was temporary. The introduction of new, labour-saving machinery further reduced the opportunities for work.

Insufficient attention, the author argues, has been given to the consequences. Those driven out of their homes in the country were left with no option but to migrate to the towns and sell their labour to whoever would pay for it. In effect, land enclosure created a market in land; landlessness created a market in labour. These are the foundations of our modern market economy. The author asserts that the harshness of the early years of the industrial revolution were the product of land enclosure which the welfare state has to some extent mitigated, although at the cost of creating a dependency culture in contrast to the sturdy independence of Clare’s parents’ generation of farm workers.

______________________________________________

Author Details

R S Attack worked as a legal secretary. Concerned about social injustice and unconvinced by the solutions of Left and Right, she enrolled for a degree in Economic History at Sussex University. There she was able to do the research which underpins this book. As a poet herself she found in John Clare a kindred spirit with a poet’s perception of the beauty of nature and a clear vision of the injustice wrought by the enclosure movement.

______________________________________________

Reviews

‘John Clare is generally recognised as a fine lyrical poet, who wrote idealistically about the English countryside, whilst contriving to overcome his extreme poverty and the unstable circumstance of the times. This short but powerful book reveals how inadequate such a view is of a man whose most abiding passion was for economic justice, rather than for literary success. He had indeed a gift for the lyrical, inspired by the beauty of his native land in Northamptonshire; yet even such poetry he described as kicked out of the clods’. Freedom was indeed his life’s message to the world, but it was the freedom to live and work on land not subject to a master and landlord. His was the great lost cause of free land. And yet, even today, the cause is not finally lost. Clare’s poetry, with the aid of such books as Rosemary Attack’s, may reveal to a new generation, the need to return the land to its true heirs, the people of England.’

Land & Liberty